But not all overseas publishers working in English operate at the lowest end of the value chain. Bored Panda publishes viral content about art, design, and other topics. It frequently works with the original artists to create stories.

The company was founded in Lithuania, and that's where the majority of its staff is based. The editorial staff of Bored Panda have a content-generating activity of asking the "Bored Pandas" questions that entice participation, for instance, "Hey Pandas, What Is The Best And Worst Feature Of The People In Your Country? " or "Hey Pandas, What Is Your Favorite Classic Arcade Game? That is done because, to get the maximum interest for an article, it has to involve or draw content from the greatest number of users. As a result, many upvoted, popular articles are about X number of times people have done XYZ, or X people who have done XYZ good, bad or weird things, or X number of dogs or cats that have done whatever.

These "aggregated" articles are drawn from Bored Panda user submissions and sorted out through a process called content curation, which is also done to articles sourced from other websites. The contents is then organized in order of relevance and popularity, with the bottom-listed items available for viewing with a click. That is the right way to do it in that the information source is still cited.

While reading about biases in the the article called 'Biases Make People Vulnerable to Misinformation Spread by Social Media'. What attracted by attention the most was the concept of bias in society. It refers to the way bias that exists among a certain friend group starts to influence on the way they interpret various information they receive. I tend to follow people who are on some level similar to me, and it sometimes shocks me when I come across accounts of those who are the polar opposite.

When I read what they have been posting, I always believe they are wrong. This is the clear example of the 'us and them' distinction mentioned in the article. For years, people in the Philippines and other developing countries performed menial tasks for Facebook, such as reviewing content to see if it violates the social network's terms of service. They have also toiled in the gray and black markets created by platforms.

Some create and sell fake social media accounts, while others offer services to spam Facebook groups with links to try to generate traffic. BuzzFeed News recently spent $10 to purchase 100 fake Twitter accounts from a man in Indonesia. Your mental health should be your priority, but you shouldn't rely just on social media to get all your facts.

Just like any other website, TikTok has its fair share of awesome and educational content that's mixed together with utter garbage and even fake news. Ex-Soviet refugee and psychology expert Dr. Inna Kanevsky is calling out the latter in her own TikTok videos. The series was produced by Philip Davali and Ólafur Steinar Rye Gestsso, who were assigned to complete the piece by the Danish photo news agency Ritzau Scanpix.

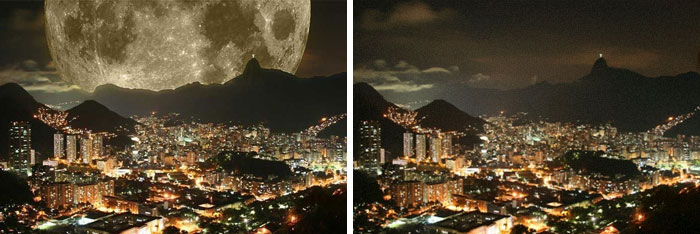

It was born out of the heated debates we've seen—and even written about recently—around images that allegedly show people flouting social distancing guidelines. Whether it's a photo of a "crowded" beach in California, or viral photos used to shame people on social media, it's all too easy for these images to be deceptive in nature. How 41 People in Lithuania Took Over Your Facebook FeedThe Shift.

Kevin Roose, Nov 30, 2017, New York Times The company, Bored Panda, might not be familiar to you. But if you have a Facebook account and a pulse, you've probably seen its handiwork. Lightweight and inoffensive posts like these have made Bored Panda one of the biggest attractions on Facebook.

Its page received more than 30 million likes, shares, comments and reactions last month, far more than companies like BuzzFeed, CNN and The New York Times, according to NewsWhip, which compiles data on social media publishers. Its website had 116 million visitors in October, according to its internal analytics. I've spent time with Facebook's news feed ranking team, and these days it's full of smart people working hard to figure out what users really want and deliver it to them. It just happens that building an algorithm to rank stories according to things like accuracy and substance is extremely hard—perhaps impossible. In response, Facebook tweaked the algorithm that determines which stories appear in its News Feed, and traffic to most viral publishers plummeted.

Now, the easiest way to go viral on Facebook is with political news designed to provoke outrage and fear. That is, unless you are the one viral publisher that has defied the algorithm and thrived. Against all odds, Bored Panda, a blog started by a Lithuanian photographer in 2009, remains among the top publishers on Facebook.

I'll leave it to computer scientists to judge Google's algorithm. But the rise of the coded gaze has implications that go beyond the details of any one app. As my social-media timelines filled with images of my friends with their doppelgängers, I was struck more by their photos than the matches. They were often alone, poorly lit, looking straight into the camera with a blank expression. In my own match image, I have a double chin and look awkwardly at a point below the camera.

Next to my washed-out face, Ryusei's painting looks shockingly vivid, right down to the vein in his subject's forehead. Unlike the well-composed selfies and cheerful group shots that people usually share, these images were not primarily intended for human consumption. They were meant for the machine, useful only as a collection of data points.

The resulting images of photographed face next to painted face, with a percentage score indicating how good the match was, seemed vaguely diagnostic, as if the painting had materialized like the pattern of bands in a DNA test. Judging by the flattered or insulted reactions on social media, many people saw their matches as revealing something about themselves. For example, the content of Bored Panda is copied to another identically structured website, which started in 2010 and is also managed from Vilnius, called DeMilked – Design Milking Magazine. What the link is, I do not know, it might be legitimate since Bored Panda was founded to promote art and design and DeMilked supposedly focuses on that – it might be a sub-brand.

However, Bored Panda's articles are republished and reposted all over the Internet, from the Daily Mail to personal and business pages on Facebook, often without mentioning Bored Panda as the source or giving the name of the author. It's spending millions of dollars on sponsorships and other initiatives in the news industry. The company also recently revealed that publishers using its fast-loading Instant Articles are earning roughly $1 million per day in revenue. Google and Facebook now say they are both working on ways to help news publishers earn money from subscriptions via their platforms. Sometimes overseas publishers mix their topics to puzzling effect. A website called USMedicalCouncil.com shows new visitors a pop-up message to like the Fibro & Chronic Pain Center Facebook page.

That page constantly posts articles connected to health spammers in Pakistan. However, USMedicalCouncil.com recently switched topics and now posts hyperpartisan political stories. One of its most recent is a completely false story alleging incest in the Trump family. Native American publishers aren't the only ones competing with — and sometimes losing out to — overseas publishers in a niche aimed at people in the US. As previously reported by BuzzFeed News, the town of Veles, Macedonia, is home to dozens of websites targeting American conservatives which often publish fake news.

A recent BuzzFeed News analysis of partisan political news websites and Facebook pages revealed that a page run by a 20-year-old in Macedonia outperforms many of the biggest conservative news Facebook pages run by Americans. BuzzFeed News has also found publishers in Kosovo and Georgia that publish news crafted for American conservatives. Some internet headlines are simply designed to be incredibly attention-grabbing. These brilliant clickbait examples from social media and the web in general will show you why certain techniques work to get people to click on links and read articles. The company recently released the 'What to Know for Facebook Publishing Ahead of 2019' report, digging into how the social media network's algorithm changes de-emphasise some forms of viral news content and shortform video. Publisher-centric social media research company NewsWhip has taken a deep look at the damage caused to media companies by Facebook's NewsFeed algorithm changes earlier this year.

Despite Facebook reducing news on the NewsFeed from 5% to 4% earlier this year, the research shows how publishers have adapted. For the most part, however, the names in my list above are little more than a vague memory and the subject of the occasional retrospective. "Testimony via Gianni Giardinelli" is what can be read at the bottom of the text in some of the earliest versions. A search on the internet shows that Gianni Giardinelli is a French actor of Italian origin, living in Paris.

On his social media accounts, there is no trace of this testimony. Could the source mentioned be another person with the same name? Yes, but there seem to be no ways of contacting this person. Bored Panda has compiled a list of fake viral photos that fooled internet users everywhere. From marijuana in space to bears chasing cyclists, some edits are so well made, you'll have a hard time believing it's fake even with the real picture right next to it. More stuff in your feed from mom, dad, and your close friends, and fewer whacky videos, news articles, and memes.

It's not just Facebook's attempt to end its fake news problem. It's Facebook's attempt to erase practicallyall news from the feed to give users a sense of community, not outrage and clickbait. Now Facebook is doubling down on that theory with a drastic change to the News Feed algorithm. In the coming months, Facebook's algorithm will no longer prioritize content from news publishers and brands. Instead, you're more likely to see posts from people you're connected to that will drive engagement through comments and discussion, not shares and likes.

Researchers at the Engaging News Project studied how 2,057 adults in the United States responded to clickbait news headlines. Examples ranged from political stories to junk science topics. They found that headlines indicating future uncertainty were among the most likely to get people to click and share the article. People naturally want to satisfy their curiosity by finding out more about the topic.

Even Jason Momoa, the actor who's physique looks like it's been genetically engineered to make other men feel inferior, is body-shamed. Internet strolls started attacking the 39-year-old Aquaman star on social media after someone leaked a shirtless photo of him. As the hate grew, more and more people stood up to defend their beloved star. A series of deepfake videos of Tom Cruise are going viral on social media. The videos, posted to TikTok over the past week, appear to show the actor engaging in a number of innocuous activities. In another, he practices his golf swing, and in a third, he relates a joke to listeners.

The format quickly devolved into a cringe-inducing punchline. The idea of this article came from a recent photo series I saw on BoredPanda about viral photos people thought were real but were fake. It reminded me of some of my photos people always call fake. Realistically, it makes more sense to take Facebook at its word that this test is chiefly about figuring out what its users want. And it's entirely believable—especially in this age of still-overwhelming click-bait—that users want more posts from their friends and fewer from the publishers that are constantly pushing provocative headlines in their face.

Over the past five years, as it has grown into a dominant source of online news, Facebook's news feed has reshaped journalism in profound ways. Its algorithmic rankings, which determine what news its users see , rewarded outlets for framing their stories around provocative or outrageous headlines. Outlets accustomed to building long-term reader loyalty through accuracy and nuance found their business models undermined by this system, which made little effort to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality sources of information.

Reflecting on this made me realise that "fake" is pretty much at the heart of what I do in user experience. I don't mean this in the pejorative sense of "fake news". I mean it in the same way that theatre or cinema is fake.

Many of the projects I work on use metaphors to help people better understand a system. We may live in a post-skeuomorphic world but metaphors like the "shopping basket" are still used in abundance. You might recall Bored Panda's smart, witty and entertaining videos on Facebook . Aside from Facebook though, Bored Panda has been around for quite some time and focuses on art, design, photography, community and bringing creative people together.

When I fired up the app, I was initially less interested in finding my doppelgänger than in what the result might say about the current state of facial-recognition algorithms, which are famously bad at parsing nonwhite features. My last foray into face-matching involved an app called Fetch, which purported to tell users which breed of dog they most resembled; many of my Asian friends and I were told we looked like Shih Tzus. Not long ago, Buolamwini highlighted the story of a New Zealander of Asian descent whose passport photo was rejected by government authorities because a computer thought his eyes were closed.

The psychology professor, who works at San Diego Mesa College, debunks psychology fake news over on TikTok in a blunt yet witty manner. Her videos have earned her a following of nearly a million people on the video-sharing platform. They've also gained popularity elsewhere as well, including on Reddit where a post about her amassed a whopping 130k upvotes in just 2 days.

There are also some American and British companies taking advantage of the overseas information explosion by using relatively cheap labor in the Philippines or India to create content for their websites. BuzzFeed News recently revealed that the content for International Business Times Australia is actually produced by writers in the Philippines. Its parent company, Newsweek Media Group, which publishes the magazine of the same name, also employs writers in India to create content for its global IBT editions.

One overseas writer for an IBT website told BuzzFeed News they are required to write five articles per day. He denies telling students to publish fake news, but does instruct them to copy a few paragraphs from a story that's performing well on Facebook and create a new story from that. It's the content equivalent of an overseas factory pumping out knockoffs of the latest fashion trend. One way the content from this network of sites spreads is to have fake Facebook accounts share it in Facebook groups about health topics. Thompson pointed BuzzFeed News to several accounts that were part of a group of interconnected profiles that consistently share articles from the same health sites into Facebook groups. Some of the accounts are also administrators of these groups, which focus on mental health, fibromyalgia, addiction, and medical marijuana, among other topics.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.